“My life was to be many things. But it was never grey.”

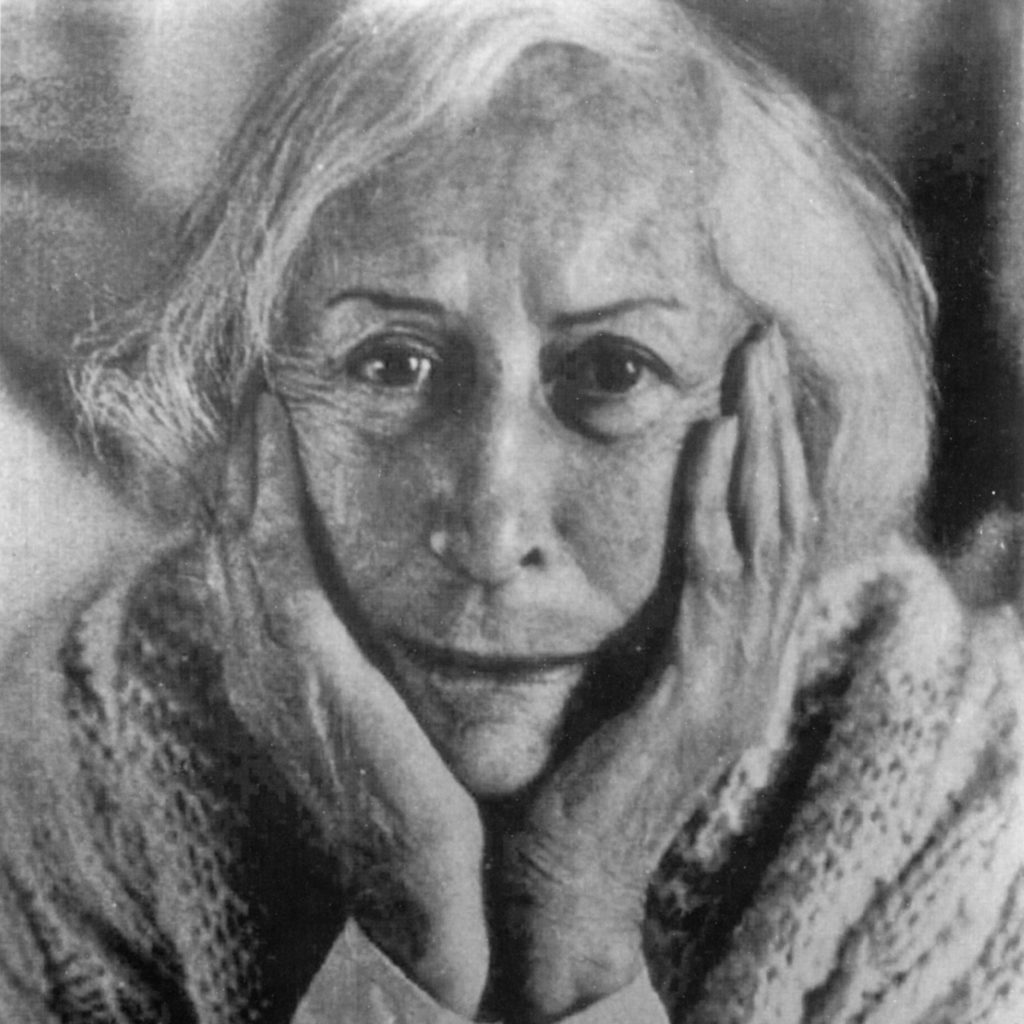

Umm-El-Banine Assadoulaeff, known as “Banine,” who immortalised her childhood in early 20th century Baku in her memoir, Days of the Caucasus, lived through the 20th century’s most defining moments. Her extraordinary life was shaped by fortunes made and lost, violence and flight, which shaped her work as a writer.

By the age of 18, Banine had inherited and lost a vast fortune, been forcibly married, abandoned her husband, and fled across Europe. But the loss of the country of her birth, though it forever defined her as an exile, proved to be her rebirth.

Born in 1905 in what was to become Azerbaijan, the youngest of four daughters, Banine was the granddaughter of oil industrialists on both her mother and father’s side. Her family was rich even by the standards of the opulence of the time. An oil boom in Baku in the late 19th century had spawned dozens of millionaires. Banine’s maternal grandfather, Musa Nagiyev, who discovered oil on his farm, became the richest of them all, almost overnight.

Though her childhood was one of luxury, flight was its earliest marker.

In 1905, the Armenian-Tatar massacres in Baku forced Banine’s heavily pregnant mother, a Muslim Tatar, to flee the capital for the relative safety of the remote region of Karabakh. This brought on her labour, in a region, as Banine wrote in an article for le Monde in 1990, entitled “The Azeri point of view,” “where there were no doctors, no hospitals, where she gave birth and died from lack of medical care. That child was me.”

It was, Banine wrote, the foreshadowing of many flights to come.

While her father, Mirza Asadullayev, instilled a love of Western ways, his work – a prominent businessman, he was to become a minister in the short-lived Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan – meant he was often absent. Discipline, and the standards of behaviour expected of a Muslim woman of her time, came from her grandmother, “a fat, authoritarian woman.” A loving Baltic German governess, Miss Anna, gave her a love of learning. A bright pupil, the young Banine soon showed an aptitude for foreign languages.

The Baku of Banine’s birth, which she recollects with the curious mixture of detachment and nostalgia of one long-exiled, was marked in equal measure by opulence and violence. The oil rush, with its promise of wealth, attracted for a time a cosmopolitan set to Baku, within its background, a constant rumble of turbulence and tension.

“In Baku, the majority of the population of Armenians and Azerbaijanis were busy massacring one another,” she wrote.

She described a violently patriarchal society with cool detachment. Ethnic violence is an occurrence barely worthy of a mention.

With the innocent cruelty of children, the young Banine and her two cousins “played at massacring Armenians, a game we loved above all others.”

The family’s extreme wealth allowed it, for a time, to remain oblivious to the conflicts that were tearing Europe, and Russia, apart.

“The champagne flowed freely, to use the classical phrase,” Banine wrote in her memoir, “thus our world marched toward disaster.”

By 1914, with the stirrings of the Russian revolution, the Caucasus became “full of Russians.” The Czar’s abdication, and the emergence of an Armenian-led military dictatorship, led Banine’s family to flee, before returning for a brief period as Azerbaijan becomes an independent republic in 1918.

It is then that the death of her grandfather turned the teenage Banine into a multimillionaire, “but only for a few days, for I was soon woken at dawn by ‘The Internationale’ sung in the street.”

The Russian Revolution had caught up with Baku. Independence, like Banine’s fortune, would prove to be short-lived.

The fall of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in 1920 brought about an abrupt change. Banine’s father was jailed by the new authorities. The 15-year old Banine was forced to marry a man she detested, in return for him arranging her father’s release.

Another flight soon followed. First, that of her father and sisters, and in 1924, after months of waiting for a passport, of Banine herself. After leaving Baku for Istanbul, she boarded the Orient Express alone, leaving her husband behind forever.

Banine’s Days of the Caucasus closes with her arrival in Paris. But for Banine, another life, rich in experience if not in material wealth, had begun. Reunited with her sisters and father, the jewels and assets they had been able to salvage were soon sold, and Banine had to find work to support herself.

Banine’s sequel to Days in the Caucasus, Parisian Days, which is yet to be translated into English, describes Paris in the 20s as a city of exiles, teeming with Russian emigres, who had fled the revolution, driving taxis to support themselves. In this community, a diaspora of the once rich, Banine, still in her teens, learned to make her own way in the world.

A job as a shop model followed, allowing Banine to support herself. Her life in Paris, which she was to call home for the rest of her life, had finally begun.

In the Paris of the 1920s and 30s, Banine found the intellectual life she craved. Many of the century’s greatest writers, from James Joyce to Hemingway, seeking freedom, adventure, and the company of their kind, called the city, for a time, their home. Those literary circles were a strong influence on Banine’s work. While eking out a living as a secretary, model, and salesperson, she started work on her memoir.

The publication of a first novel, Nami, in 1943, first made her name known in literary circles.

But it was her publication of Days in the Caucasus in 1945, followed by Parisian Days two years later, which brought her success. Famous writers such as Andre Malraux, Ivan Bunin, Nikos Kazantzakis, and Ernst Jünger wrote her letters of support and admiration. With Jünger, at times controversial German philosopher, with whom she shared hatred of Bolshevism, this was to mark the beginning of a 50-year friendship.

Her flat in the Rue Lauriston, in Paris’s 16th quarter, which she lived in for decades, became a meeting place for the century’s greatest minds.

Nine further books followed novels and several books about Jünger. Banine was also a prolific translator, helped by fluency in French, English, Russian and German.

At the age of 50, she converted to Catholicism, a faith that inspired her last work, What Mary told me, published in 1991, a year before her death.

She died on October 23 1992, aged 87, in Paris. She had never returned to Azerbaijan since she left it in 1924. Her father, sisters and a younger half-brother are all buried in the city she called home for more than 60 years.

Days of the Caucasus, first published in French in 1945, was translated into English and published by Pushkin Press in 2019.