By THOMAS GOLTZ

BAKU/LIVINGSTON, MONTANA

Thomas Goltz is one of the best-known writers on the Caucasus region. He is a trained Shakespearean actor, and predictably, legendary for eccentricity and drama.

His works include Georgia Diary, Chechnya Diary, Assassinating Shakespeare, An Oil Odyssey: A Geopolitical Motorcycle Adventure Down the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Oil Pipeline, and Turkey: The Bridge. He is preparing a book on Syria and the Middle East, entitled “Zakhrafa: Memories of a Disappearing Middle East”.

But Goltz is perhaps best known for his first major work, Azerbaijan Diary (1998). He first arrived there in 1991, rather by chance.

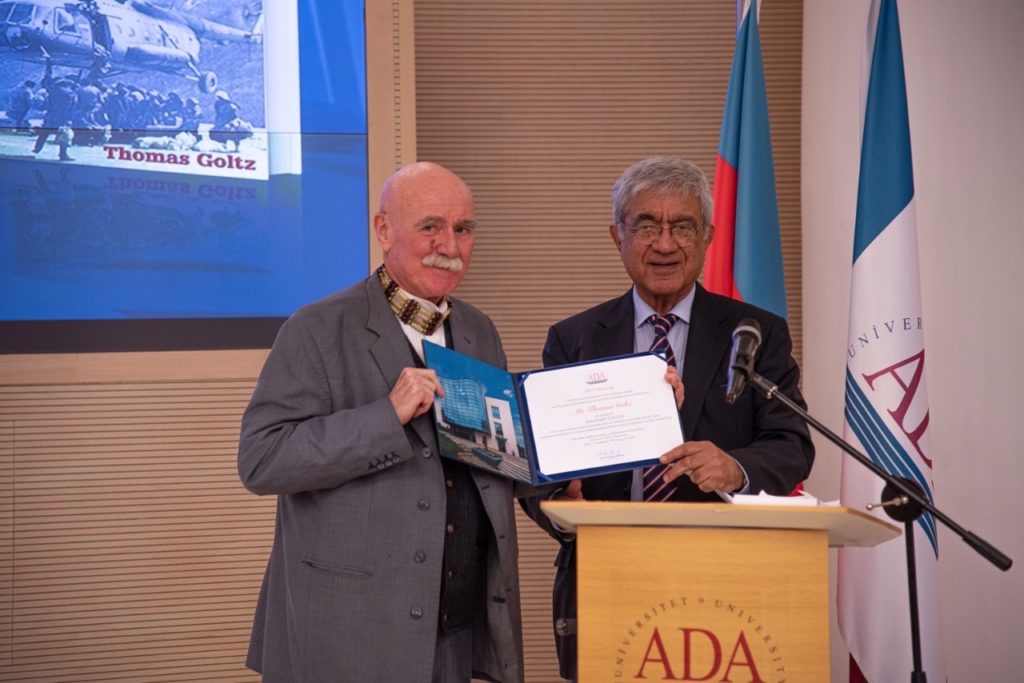

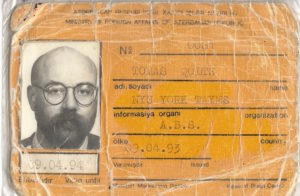

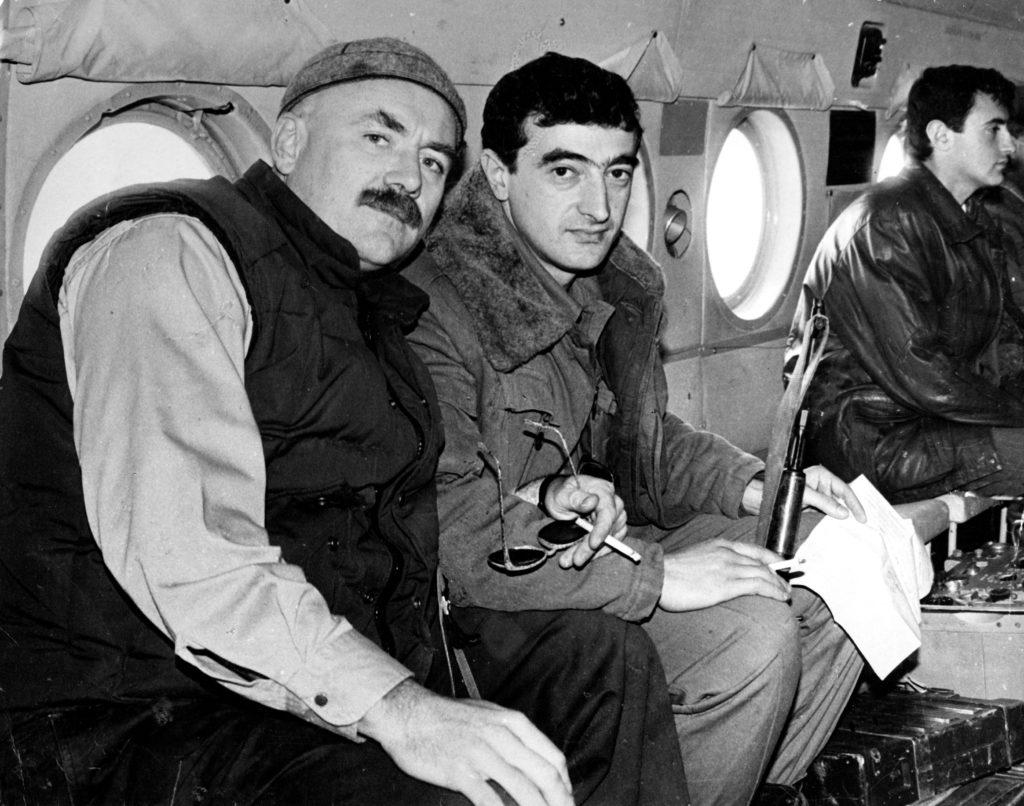

In 2020, he was awarded an honorary PhD by the Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy (ADA). He was the first foreign correspondent ever officially accredited to Azerbaijan, with an accreditation card number reading “0001”. As well as one of the first to meet and interview the late national patriarch, President Heydar Aliyev, in his home region of Nakhchivan after the Soviet demise.

Now 66, Dr Goltz still frequently visits Azerbaijan.

Below, he retells a story about one of his first adventures in the country – a trip aboard one of the last trains between Baku and the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan. The route has been closed for 30 years because of the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Ironically, it is at the forefront of a dispute between the countries. Azerbaijan says Armenia is reneging on an agreement to reopen the route as part of a peace settlement and effective Armenian capitulation late last year.

LAST TRAIN TO NAKHCHIVAN

The train was grimy—a decaying East German half-wreck. My Azerbaijani friends took me to Baku station. They forced smiles as I boarded the death-trap rail car. They waved. I smiled through a wagon window with no glass panes, shot out or just thrown out.

As the train pulled away with a woo, woo, some of my comrades wept from the platform. I didn’t know if these were tears of joy or sorrow.

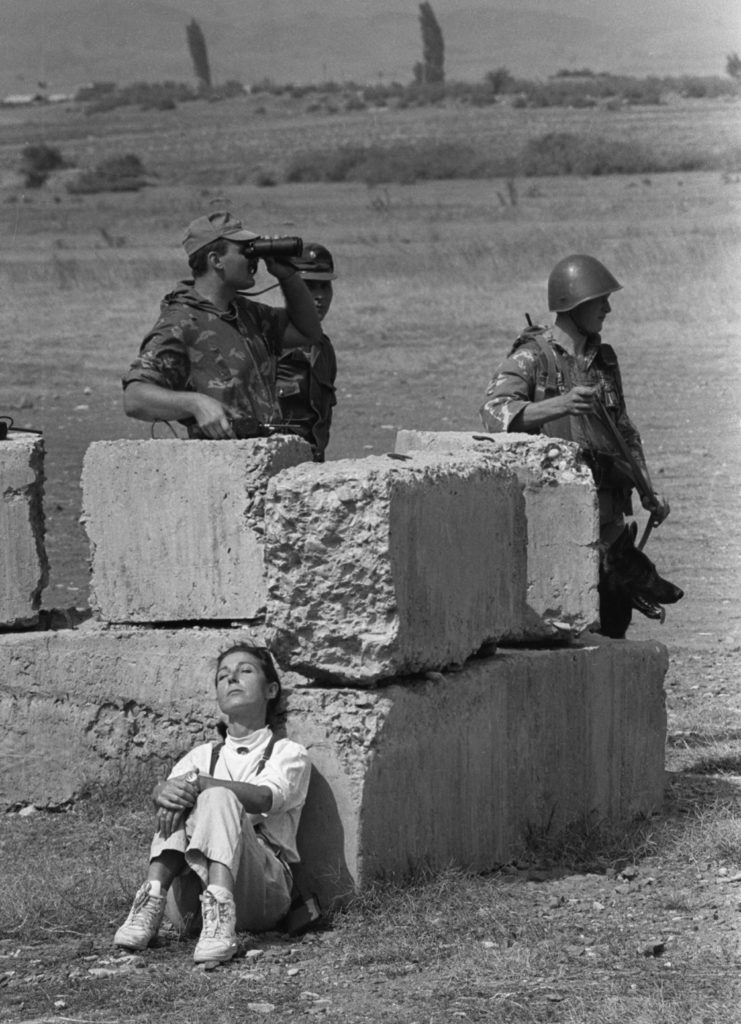

Sorrow and trepidation, it turned out. I was still new in the country but no stranger to war zones. A bit oblivious. But the train was, after all, headed to Nakhchivan.

Nakhchivan, the Azerbaijani exclave bordering Iran, Turkey, and of course, Armenia. Our rickety train would cross through a rocky, forlorn 40-km strip of Armenia called the Zangezur corridor to get there.

The two countries were still a few months from independence but effectively at war over the Azerbaijani Nagorno-Karabakh region. A war that would widen for three decades.

And only fools rode a war-zone train known to be strafed with random gunfire or face booby-trapped rails. I was among their number.

The carriage compartments were truly filthy, the toilets an outrage to olfactory decency and the only remedy seemed to be to smash out a remaining window for some clean air. This made the night ride chilly.

Little did I know this smoking, derelict locomotive would be among the last to make the trip from Baku to Nakhchivan. Soon the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan would go full-blow. It’s been 30 years since another train plied those iron tracks.

Nakhchivan is often dismissed as a minor Azerbaijani “exclave”. But waking up, one can see why it is coveted. A virtual oasis on the Araz (Araxes) River. Amid scorching desert and steppe, the river gives life to a bountiful variety of palm trees, lush mountain peaks, and isolated, picturesque villages wrapped in vineyards, mulberry trees, and peaches from which locals proudly make moonshine (tutovka).

Of greater interest was when our train first began to skirt the Araz River basin on the Iranian frontier, looking out into the Islamic Republic. Then we pulled into and then out of a stopping station on the Azerbaijani border with the neighbouring Armenian province of Meghri and the “Zangezur corridor” linking it to Azerbaijan’s Nakhchivan.

Things then got rougher.

New passengers clambered atop our filthy train with busted-out windows—Soviet border troops, riding high on the carriages, AK-47s at the ready to secure our passage, lest local Armenian militias attack our train.

Protected by Soviet troops, our “Last Train to Nakhchivan” made it through the gauntlet, pulling into the main town to shouts of joy and whistles. The great fanfare was due to a simple fact – the train had actually made it intact.

But I had not come for some sightseeing gig.

NATIONAL ICON IN QUASI-EXILE

I was there to hunt down a certain Heydar Aliyev. Though his pictures, statues, and likeness are now everywhere, and almost every main street or park in regional towns have been renamed in the late leader’s honour, at the time, he was generally regarded as a disgruntled former Soviet Politburo member.

Having left the Politburo under unclear circumstances in 1987, he retreated to his home in this isolated exclave, biding his time. He had returned from Moscow only in 1990 and now took on the mantle of a fighter for the independence of Azerbaijan.

Heydar Aliyev was often referred to as ‘the first Turk’ in the Kremlin,’ – owing to Azerbaijani’s Turkic language roots – before being effectively sent into exile in one of the most obscure corners of the USSR.

But as remote as Nakhchivan is, it is also known as a cradle of Azerbaijani political and cultural figures. The man in power at the time, Azerbaijan’s first President, the pan-Turk Albufaz Elchibey, also hailed from Nakhchivan.

A former dissident and anti-communist, the two had essentially traded places, and could not have been more different in style, substance, or temperament. Elchibey, a chain smoker and copious drinker, was a virulent anti-communist who spoke little Russian. Aliyev, the consummate, wily Communist Party man who was known at the time for such things as once mentioning Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev’s name more than 100 times in a single speech. At the time, this was considered nothing surprising.

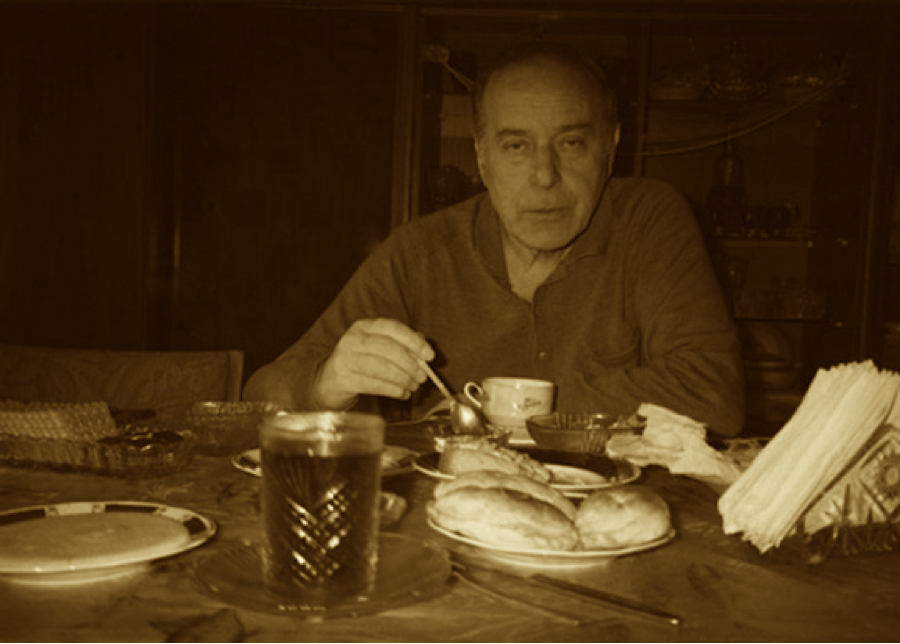

DINING WITH ALIYEV

I made my way to see the deposed Politburo man, who was then living in a pedestrian three-storey walkup – spartan for a man who was once among the 10 most powerful in the USSR.

Sipping tea over our breakfast, he railed against Mikhail Gorbachev, who came to power in 1985. Heydar Aliyev said that Gorbachev was basically a fraud. He said that the concepts of “glasnost” and “perestroika” had actually begun earlier, and more quietly, under the late Yuri Andropov, a former KGB chief.

He also slammed Gorbachev for acting unilaterally, without consulting people who were more informed about certain subjects than he was.

One was the brewing and soon to blow conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Azerbaijani Soviet Autonomous District of Nagorno-Karabakh.

“I was the leader of Azerbaijan [its Soviet Communist Party] for 14 years”, he told me. And as such was also the leader of Karabakh. I was often there and had good relations with the local Armenians. Had Gorbachev asked at the time about Karabakh, I would have expressed the realities of the situation to him. But he didn’t ask because he wanted to give Karabakh to the Armenians.”

Heydar Aliyev explained that Gorbachev had no conception of the underlying ethnic tensions in the USSR and that they needed to be managed very carefully. Instead, he said, Gorbachev essentially blew the situation through a bungling, clueless approach.

The semi-exile would not last long. Elchibey was forced to resign in 1993 after a string of losses to the Armenians. To the rescue came Heydar Aliyev, first as a temporary leader and later as formal President.

A JOURNEY OF FATE

Often, I am asked how I ended up in Azerbaijan in the first place.

It was purely by chance, “fate”, or “Kismet.”

Because the Soviet system was breaking down, visa procedures had become nonsensical. My Turkish wife Hijran and I were not allowed to board a plane from Istanbul via Moscow to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, where I had a year-long teaching fellowship lined up.

But in the chaos of those days, there was no rule which could not be broken. So – flying to Baku en route to Tashkent with a stopover was possible – well, at least it was worth a try. We eventually made it to Tashkent, but my fellowship gig turned out to be something of a scam; our apartment was a hovel, and promised benefits were not produced. We stayed just a couple of weeks before heading back to Baku.

A shaven-headed, hulking American speaking fluent Turkish- with a Turkish wife – was – in those early days – a curiosity piece, to say the least, and a “Turkic” brother. We were greeted with smiles at Baku’s international airport and no questions.

Hijran and I “arrived” in Baku on a rickety Soviet airliner full of local small-time traders bringing back Turkish goods to Azerbaijan.

Friends of friends met us, speaking in Azerbaijani, which many people mistakenly think is essentially Turkish. It is not. These unknown friends met us with Azerbaijani phrases, which in Turkish sounded curious to our Turkish-trained ears. “We have been greatly eyeballing you something-something,” said one, which in Azerbaijani simply meant “We’ve been looking forward to your arrival.”

Some early days were equally perplexing. Our hosts first put us up in a Baku suburb called Mashtagah, then famous as the centre of the Azerbaijani cut-flower “mafia” and Iran-stoked Shiah revival, and at the height of the Ashura. It was a very curious time to be introduced to Azerbaijan indeed.

We later set up camp on a cheap, dank, smelly prostitute haunt – a ship parked in Baku Bay, which in better days had done runs to Turkmenistan across the Caspian. It now was serving as a low-budget hotel – by the day or by the hour.

Hijran spent much of her time fending off hordes of con artists and prostitutes hanging about the halls.

On Day Number One (or two) in our Mashtagah bolt-hole, our “host lady” served up twin bowls of delicious borshch.

But she had a tiny apology. “I’m sorry,” she said. “But this soup has a lot of snot in it.”

That is what our Turkish-Turkic ears heard; what our hostess was apologising for was that she feared that there were too many bones.

“Sümük” in Azerbaijani means “bone,” or “kımık” in Turkish, while “Sümük” is indeed translated as “snot,” as in the “snotless meat” (hamburger) sold in butcher shops throughout the land.

All these lingual “false friends” were funny for a while and then were not.

This also resulted in my first meeting with Heydar Aliyev, who always said that he was glad to see me make the effort to see him in situ in self-isolation (although I suspect that Hugh Pope owns this accolade, then of the British Independent, a year before my Nakhchivan arrival, to give credit where credit is due).

Much has changed since then.

We could start with the 25-odd years of Armenia occupation of Azerbaijan’s Nagorno-Karabakh district and adjacent regions of Azerbaijan (I hate that Russian adjective and prefer ‘Mountainous’ or “Upper’ for the Karabakh region) of 1991-94 or dive into the Azerbaijani re-conquest of said territory in the so-called 44-day war of September-November 2020.

Much has been written about the military aspects of the successful Azerbaijani campaign (the use of Israeli and Turkish drones) but relatively little about the November 10th cease-fire deal between the two belligerents negotiated by the Russian President Vladimir Putin.

One item—and an important one—was the re-opening of transit corridors between the two post-Soviet states.

Arguably, the most important of these would be the railway link between “mainland” Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan that I had travelled down in that late Soviet summer of 1991, that would now (theoretically) link Turkey to Central Asia, expanding a grand New Silk (or Steel) Road.

The early stuff related above is just the tip of the iceberg. Yes, I was a “war correspondent” doing the Big Nasty in places like Xodjali and Kelbajar … but I would like to think that I managed to uniquely “embed” myself into Azerbaijani society and culture. Mugham, theatre, opera and even futbol (soccer). I have many “war” friends, but I also have a lot of “non-war” friends and just a lot of really devoted friends/fans in Azerbaijan who actually care about me.

This is huge.

Some years ago, I got an email from some California-based Azerbaijani gal. An American friend had given her my Azerbaijan Diary. It slept on her bookshelf for a year or two before she finally picked it up in boredom.

“What can this foreign journalist tell us about us?”

I paraphrase: “Dear Mister Goltz, after avoiding it for years, I finally picked up your book and finished your book towards dawn. You found us. Thank you.”

Ain’t no better review than that.

As for the “Last Train to Nakhchivan”, I would like to be one of the first passengers on the return journey.

Dr Goltz is currently quasi-quarantined in Montana at work finishing Zakhrafa—Memories of a Disappearing Middle East (Syria, Egypt and Iraq), the third book in his “Covid Quartet.” Already in print/e-book format via Amazon/Kindle are “Türkiye Diary—The Bridge” and “An Oil Oddysey—A Motorcycle Adventure Down The BTC.” The fourth element of the “Quartet” is a return to the post-Soviet Caucasus with the working title of “Between the ‘Trans & the ‘Stans,” available via Amazon/Kindle late summer 2021.