BAKU

By LADA YEVGRASHINA

Hasan Huseynov was born on July 4, 1993, to his mother, Mashuga. And to the sound of artillery bombardments in a basement maternity hospital in a besieged Azerbaijani village.

His birth in the village of Dashveyshalli in the Jabrail region came as ethnic Armenian forces closed in.

His father, 60-year-old Fattah, recalls how the family spent the night huddling in the hospital.

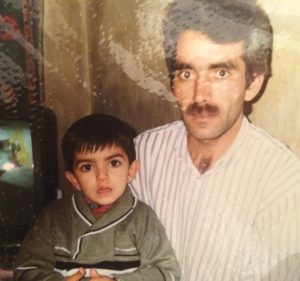

Hasan with father Fattah in early childhood, Baku

He remembers how his two daughters were hurriedly sent off in a passing car to Baku.

Hasan, then days old, of course, does not remember these nightmarish times. He has spent much of his 28 years working in Baku and Ukraine.

His parents, whenever possible, try to provide him with a cloudless childhood and youth, yet not forgetting to remind him of the land of his ancestors – the land they were driven from.

But this is a story more about the drive by his father to return home to a wrecked region at any cost.

Fattah in front of road sign leading to de-occupied areas, 2021

PICTURESQUE, RICH AREA

By August 1993, the Jabrail region fell completely under Armenian occupation, which lasted 27 years.

The village lies along the Azerbaijani side of the Araks (Araz) river, across from Iran.

The area was once an important transport hub.

During the early days of the “Karabakh war” in the early 1990s, the railway tracks were dismantled in some places, and the roads became unusable.

Nearby lies the strategically important Khudaferin reservoir, as well as many underground mineral water springs.

A rich agricultural area, in better times it produced grain, viticulture, and livestock breeding.

Most notably, perhaps, is the stunning architecturally unique medieval bridges made of stone – long-closed – crossing the river into Iran. There are round-shaped 14th-century burial tombs and 19th-century octagonal ancient baths close by.

OCCUPATION YEARS

Under occupation, the area was systematically looted and mostly dismantled, the fate of many such areas. The 50,000 Azerbaijanis in the area were forced to flee. There was a much smaller population of non-Azerbaijanis, estimated at 1,000.

Ruins of home village, post-occupation, 2021

“In the summer of 1993, my family, and the families of my brothers and sisters were forced to flee Jabrail quickly,” says Fattah.

“We wrapped newborn Hasan in the first clean cloth we came across. The shelling was massive; there was no time to get ready. I thought that only my children and elderly parents would survive,” Fattah Huseynov told the Tribune.

The Armenians – as they did in other occupied areas – by the early 2000s began to rename areas according to some ancient alleged toponyms.

In this case, the village – destroyed and looted but with a new name – was thus called “Arachamug”, though few took this seriously.

In the mid-2000s, Armenian diaspora heavyweights got involved, still showering money on the idea of a “greater Armenia”.

Among them was the U.S.-based Tufenkian Foundation, which supplied cash to a local school.

Tufenkian representative Andranik Gasparyan – at the time – stressed that “this village is of great importance not only for Karabakh but for the entire Armenian people. since it is located on the territory ensuring the security of the Armenian side.”

This was typical of the times: appeals with those with access to free cash to erect some sort of “ancient empire” allegedly four millennia old.

GOVERNMENT DYSFUNCTION IN BAKU AT THE TIME

The pain of the Azerbaijani people from the seizure of its territories in those years was intensified by strife in the power structures of Azerbaijan and anarchy in the army.

The grandparents of Hasan – his father’s Fattah’s parents – never saw their native land again. Hasan’s grandmother died in Baku in 2004, his grandfather – in 2007.

A bitter reminder of the 1990s is a severe shrapnel wound in the leg of Fattah’s younger brother, which rendered him partially disabled.

“When the Second Karabakh War [the 44-day end phase of the 30-year conflict] began in October 2020, my 27-year-old son Hasan and I went to the military registration and enlistment office to enrol as volunteers,” he said

“But only certain categories of those liable for military service were taken to the front.”

“They explained to us that in the 21st century, the professionalism of the Azerbaijani army had grown, and it had state-of-the-art weapons at its disposal, including the latest Israeli and Turkish drones”.

The Azerbaijani army recaptured the Jabrail region at the end of October 2020.

Fattah took part in the battles for Jabrail, Aghdam and Fizuli during the first [pre-2020] phase of the Karabakh war. He barely endures parting with the land of his ancestors.

“When I learned from the press about the liberation of the Jabrail region, and later in November – about the end of the war and the return of all Azerbaijani regions, I cried and prayed to Allah so that we could return to our homes as soon as possible.

“I am grateful to the President of Azerbaijan, whose actions led to victory. For me, as a refugee, this is the most important thing,” Fattah said.

RETURN PLANS

Fattah, who just turned 60, has had a colourful life, to say the least.

“I served in the Soviet army in Mongolia, then lived and worked in Krasnoyarsk [Siberia], then returned to Azerbaijan to my parents, and got married.

“In our village, we had our own farm – sheep, cows, our own butter, milk, meat, grapes, vegetables and fruits.”

Fattah, who now works with an automobile trade like many other refugees to adapt to Baku fast. At first, we lived with my older brother, but then we started working, and I was able to build a house for my family,” Fattah told the Tribune.

Although he lived in the capital of Azerbaijan for 27 years of his life, Baku never really become his home. His roots remained in Jabrail.

“My relative was recently able to visit our village for work using a special permit. He made a video for me, which shows that our house is destroyed. In general, there are almost no whole houses left in our village.

“But this doesn’t scare me. I want to return, get a piece of land, reintroduce livestock, and buy a horse – this is my dream,” he said.

“I want to live in peace. Only occasionally might I come to noisy Baku,” says Fattah.

The State Committee for Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons has called him, asking if he and his family wanted to return, what property they had there, and asking what else they might need.”

“We are definitely coming back; I look forward to it and am ready to go at the first call. And I think that we will do the reburial of the remains of our parents so that they find peace in the land of the Jabrail region.

“My son, who studied management and the basics of business in Ukraine, also wants to try his hand at developing the region,” Fattah said.

Father Fattah and son Hasan, Baku, 2021

But for now, the area can only be accessed with special permits. This is largely due to the staggering number of landmines planted by occupying Armenian forces over the 27-year occupation. The Azerbaijan government says at least 30 have been killed and more than 100 injured in landmine accidents.

There are even more basic issues – all utilities were destroyed, including telecommunications lines and municipal water, natural gas, and electricity networks. The main roads are still under renovation.

The Azerbaijani authorities have already re-made several roads.

“We hope that by next year we will see our native places, and my son will be able to celebrate his birthday in his homeland,” Fattah said.

Though Azerbaijan drove Armenian forces from the occupied territories, there is still no final peace agreement.

“We can be peaceful neighbours. I think that ordinary people in Azerbaijan and Armenia do not want war,” Fattah said.