By Dr. Farhad Mirzayev

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Treaty of Sevres, some rather radical Armenian politicians remarked that the document somehow justified spurious and worn-out territorial claims against neighbouring Turkey. In public speeches, the ceremonial Armenian President, Armen Sargsyan, has claimed the Treaty of Sevres is still in force, thus asserting spurious and groundless territorial claims.

Dr. Farhad Mirzayev, a London based Azerbaijani international lawyer, provides his perspective on the issue.

Some of the more radical, increasingly marginalised Armenian political figures have, in an apparent attempt to appeal to their shrinking base and remain relevant, been actively speculating about counterproductive territorial claims against Turkey. Their statements appear to be aimed at throwing a wrench into the inevitable restoration of diplomatic relations between Yerevan and Ankara.

Such reckless talk about changing century-old borders has no grounds under modern international law.

One of the most disappointing aspects of this phenomenon is that this line has been promoted by the official – if only ceremonial – Armenian Head of State, Armen Sargsyan.

Unlike populist statements by some Armenian politicians, I intend here to briefly cover purely aspects of international law.

***********

The 1920 Treaty of Sevres was imposed on the now-defunct Ottoman Empire, which lost World War I to the Entente and its allies. The obvious purpose of the treaty was to humiliate the collapsing Turkish state. And to partition of the Ottoman territories among the treaty’s participants. It was imposed on the already occupied Ottoman state by Great Britain, France, Italy and the United States.

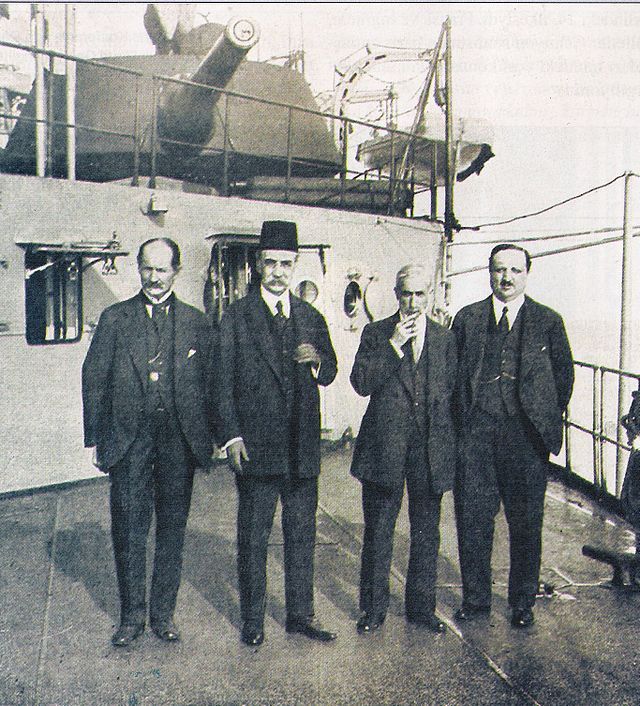

Under great pressure, the Treaty of Sevres was signed by the four delegates of the Ottoman state, whose powers were – at best – questionable under the constitutional law of the Ottoman Empire. Although some pro-Armenian sources claim that these four delegates were empowered on behalf of the Sultan, it is impossible to legally verify this fact.

In modern international law, the issues of the conclusion, validity, denunciation and succession of international treaties fall under the regime of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. It should be noted that the Vienna Convention itself is a codification of a customary international law used by states in their practice of concluding international treaties. That is, most of the provisions of this Convention are the established norms of customary international law. Simply speaking, these are long-term and approved customs of the conclusion, entry into force and denunciation of international treaties between states.

This was confirmed by the International Court of Justice in 1997 in the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Project case between Hungary and Slovakia, where the Court clearly determined that the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties “is a reflection of the customary international law”.

Articles 11 and 14 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties define that consent to be bound by a treaty is expressed by ratification. Undoubtedly, the principle of ratification is a general rule of international law, reflected in the existing practice of states and enshrined in Article 14 of the Vienna Convention. This was also confirmed by the International Court of Justice in 1952 in the Ambatielos case between Greece and Great Britain, where the Court clearly ruled that if an international treaty provides for ratification, it is a “sine qua non” for such a treaty to enter into force.

The main reason for a new requirement of the ratification of international treaties was the transitions in many states at the time, under which control over such issues was moving to parliamentary purview since the 18th century.

Obviously, this was a natural evolution to democratic governance of states by the peoples of those states. The mechanism of ratification by the legislative bodies of a state has historically developed to ensure that the representatives signing such treaties do not exceed their powers when concluding such agreements on behalf of their state.

It was from this time that ratification began to mean the formal approval by the state of an international treaty as a separate step in expressing the state’s consent to the binding nature of any such treaty. In this case, formal ratification was necessary to make the treaty legally binding. Ratification is also advantageous to the signatory state as a review period to ratify treaties before they become binding international documents. It is this time between signature and ratification that provides additional time for consideration after completion of the negotiation process.

This is important from a political perspective, including moments of a possibility of strong internal negative opinion and opposition, which may lead to the fact that a state may in fact decide not to ratify a signed international treaty.

Paragraph (a) of Article 14 of the Vienna Convention also provides that a state’s consent to be bound by a treaty is expressed by ratification. Any such treaty enters into force depending on whether such a ratification requirement is specified in its text. Paragraph (d) of Article 14 of the Treaty of Sevres provided that its ratification was required if it was a requirement under the domestic laws of a signatory state. It was designed to approve the powers of the signatories of such international treaties.

In reference to the Treaty of Sevres, Article 260 clearly established a requirement for its ratification by all concerned parties. This means that for the entry into force of the Treaty of Sevres, its ratification was required both by all participating states and by the legislative body of – at the time – of the Ottoman Empire.

In addition, according to Article 7 of the Constitution of the Ottoman state – adopted on 23 December 1876 – with the latest amendments as of August 1909, the Sultan’s right to sign international treaties on the declaration of war, the conclusion of peace, and issues related to territorial changes could only be endorsed with the explicit consent of the Ottoman Parliament.

In other words, the ratification of the Treaty of Sevres for its entry into force was also required by the constitutional law of the Ottoman state. Due to strong internal opposition and protests by the remnants of the combat-ready Turkish army under the command of Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk), the Parliament of the Ottoman Empire did not ratify the Treaty of Sevres. The Sultan never signed it. Moreover, the other signatories of the Treaty were duly notified by the Ottoman Empire that the ratification would not take place.

This is an important aspect – and evidentiary that the treaty was never ratified; nor did it enter into force for successor state – the Republic of Turkey. Another critical argument is an official non-recognition of the Treaty of Sevres by an act of the new Parliament of the Republic of Turkey by its decision of 7 June 1920.

Some representatives in Armenian political circles appeal to the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, arguing that there is nothing in this Treaty on abolishing the preceding Treaty of Sevres and the prevailing force of former over the latter one.

However, if the Treaty of Sevres never entered into force, then how can it be terminated, or how can a subsequent treaty of an independent character prevail over it? In this case all the arguments of those supporters who claim its validity are ignoring absolute requirements of international law.

The only international treaties that are effectively binding for the Republic of Turkey in terms of establishing its international boundaries are the Moscow and the Kars treaties of 1921 and the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which were signed and ratified by the Republic of Turkey. These treaties defined the limits of Turkey’s sovereign territory and international boundaries.

Such treaties establishing boundaries that have entered into force for the parties cannot be terminated unilaterally, since it is a rule of customary international law which is also enshrined in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

Under Article 62 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, the fact that Armenia became a part of the USSR and then gained independence in the early 90s as a rebus sic stantibus (fundamental change of circumstances) cannot be considered as a ground for the unilateral termination of the said boundary treaties determining the borders of Turkey, Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. In 1962 in the Temple of Preah Vihear case between Cambodia and Thailand, the International Court ruled that the principle of stability of border treaties remains prevailing even despite a fundamental change in circumstances.

Another important question: did Armenia have the right to sign an international treaty without being a subject of international law in 1920? The answer is clearly not in favour of Armenia. Under international law, international treaties are signed between subjects of international law, namely states and international organisations. The first Armenian republic (1918-1920), whose representative signed the Treaty of Sevres, was not recognised by a single state in the world – nor by the League of Nations (through membership in the organisation), and at the time of signing the Treaty of Sevres, Armenia did not have a legal personality under international law to sign such treaty. Thus, how can a non-subject of international law be a party to an international treaty? It could be also treated as an attempt to recognise the first Armenian republic. If we look at the historical evidence and carefully review all the documents of that time, it can be clearly seen that the winning states were more inclined to transfer the tutelage of the Armenian state under the mandate of the United States. This follows from the extraordinary activity of President Woodrow Wilson.

We often could come across the ill-grounded arguments of some representatives of the Armenian political establishment regarding Article 89 of the Treaty of Sevres, which provided for “Turkey and Armenia as well as the other High Contracting Parties agree to submit to the arbitration of the President of the United States of America the question of the frontier to be fixed between Turkey and Armenia in the vilayets of Erzerum, Trebizond, Van and Bitlis, and to accept his decision thereupon, as well as any stipulations he may prescribe as to access for Armenia to the sea, and as to the demilitarisation of any portion of Turkish territory adjacent to the said frontier“.

Most of those supporters in their numerous official statements claim that despite the fact that the Treaty of Sevres never entered into force, US President Woodrow Wilson rendered an arbitral award establishing new boundaries and transferring large territories from Turkey to Armenia. The referred award exists in reality and President Wilson made such a decision, allegedly based on the requirements of Article 89 of the Treaty of Sevres. However, it should be noted that clearly under the pressure of circumstances, President Wilson was in a rush with his decision, since he made it in relation to an international treaty that never entered into force.

The reference shall be made once again to the wording of Article 89 of the Treaty of Sevres, submitting the territorial disagreements between Armenia and Turkey to the arbitration of the US President, and Article 260 of the same Treaty establishing a mandatory ratification requirement for the treaty’s entry into force.

So, what is the actual result under international law?

The Republic of Turkey never agreed with any transfer of the issue of its borders to Armenia under Wilson’s arbitration, since it did not take the actions necessary under international law for the entry into force of the referred treaty.

The legal nature and binding force of such an arbitral award with respect to an international treaty that never entered into force thus seems illogical and unreasonable from an international law perspective.

Consequently, Wilson’s award could not be under any circumstances have any binding force on Turkey under international law. If we look carefully at all the diplomatic correspondence of the President of the United States during that period, especially his letters to the US ambassadors in the Entente countries, then it is obvious that he was concerned about the military achievements of the Kemalist Turkey. In such circumstances, the Allies tried to save face in the light of the military successes of the young Turkish republic. In such a case, Wilson’s arbitration decision was nothing but a pure populist step.

In conclusion, it must be stressed that we are in the 21st century and that any unreasonable historical claims to neighbour states are not in line with the requirements of the fundamental principles of international law.

Making the best efforts to start living with neighbour states pursuant to the fundamental principles of international law and good neighbourliness of spirit, and refusing groundless territorial claims would be a serious step by Armenia. It obviously would contribute to peace and stability in the region, establishing a good relationship between Armenia and Turkey.