The European Union intensified pressure on Belarus, hitting the ex-Soviet state’s sources of export income with unprecedented severity and speed in response to President Alexander Lukashenko’s diversion of a scheduled flight and arrest of a dissident journalist who was on board.

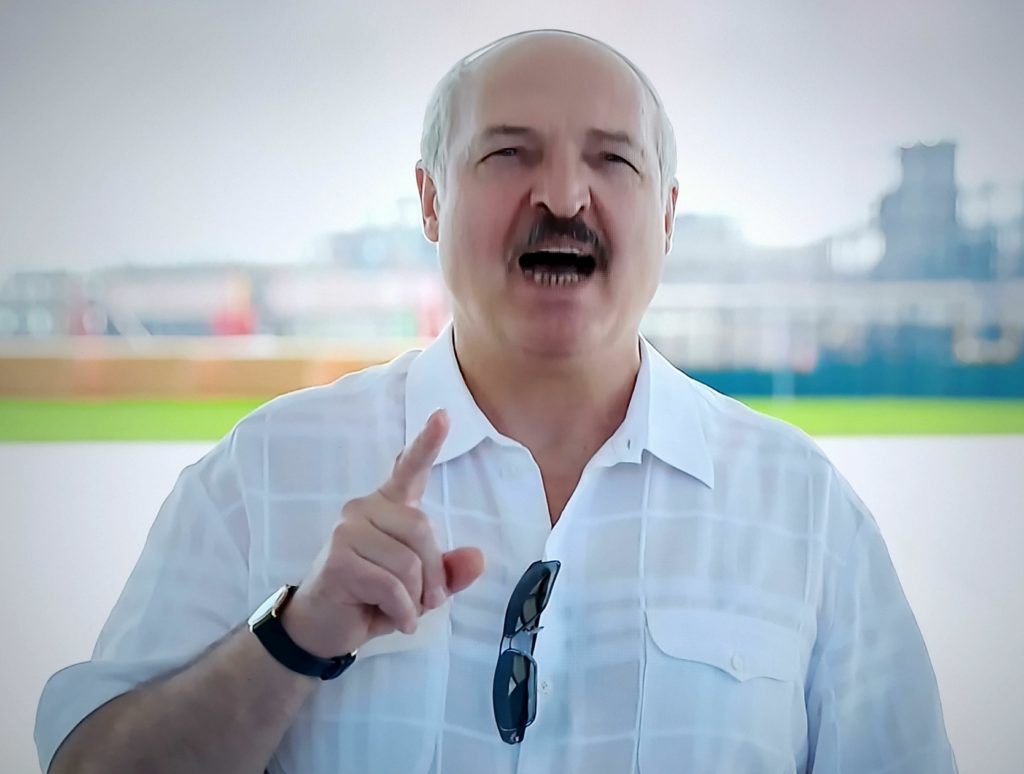

Lukashenko responded with typical defiance, vowing to show “the bastards on the other side of the border” that the country would not falter in the face of any such punitive measures.

The most serious of the sanctions took aim at Belarus’s lucrative potash industry – barring EU companies from transporting the vital fertiliser ingredient in high demand on widely diverse markets, particularly in Asia. Belarus says it provides 20 percent of world supplies and will now have to find other routes for shipping it abroad.

In power since 1994, Lukashenko has been repeatedly accused of gross human rights infringements – ranging from disappearances of his critics in the 1990s to mass detentions and beatings of demonstrators who took part in large street rallies last year to accuse him of rigging his re-election to a sixth term.

SANCTIONS TARGET ECONOMY

But previous sanctions over the years targeted the president himself and other senior officials rather than the sources of the country’s livelihood and had minimal effect on Lukashenko’s behaviour.

The latest sanctions, an endorsement of moves first approved earlier this week, followed a ban on Belarusian airlines within the EU and a call for European airlines to avoid the country’s airspace.

These newest moves were approved with uncharacteristic speed and resolve by the 27-member EU’s leaders who usually find themselves bogged down in squabbles at their summits.

The measures also stipulate that Europeans may not “directly or indirectly sell, supply, transfer or export to anyone in Belarus” communication equipment, technology or software that could be used for repression. Trade in petroleum products, potash and tobacco products is banned. Access to EU capital markets was limited, with a ban on trading Belarusian securities with maturities of more than 90 days.

The EU has now banned 166 Belarusians or officials connected with Belarus from entering or doing business with the bloc.

EU leaders were enraged by Lukashenko’s diversion to Minsk of a scheduled flight from Greece to Lithuania – a MiG-29 fighter was scrambled to order the aircraft down. Once on the ground, independent Belarusian journalist Roman Protasevich and his Russian girlfriend were detained.

A contrite and subdued-looking Protasevich has been shown on television and at a news conference admitting to charges of inciting violence in connection with last year’s protests. More than 30,000 protesters have been detained for various periods in the past year.

Accused by Western leaders of state piracy, the president has been unrepentant, saying the plane was brought down to protect his country from “open rebellion”.

DEFIANT LUKASHENKO

In a video clip shown by the state-run BelTA news agency, Lukashenko vowed that “not a single enterprise” would fail as a result of the EU sanctions.

“We have to show those bastards on the other side of the border that their sanctions are quite simply impotence,” he was shown telling officials at a dairy farm. “And we will do just that.”

His government would take whatever measures were necessary. Even a declaration of martial law if necessary, he said, without elaborating on what such a measure might achieve or the circumstances in which it might be introduced.

The EU actions were clearly targeted at hitting the economic potential of a country highly dependent on financial – and even potentially military –support from Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Jean Asselborn, the foreign minister of Luxembourg, had made a case for the punitive measures at a ministerial meeting earlier this week.

“The key word, I think, is ‘potash,’ ” he said. “We know that Belarus produces very much potash — it is one of the biggest suppliers globally — and I think it would hurt Lukashenko very much if we managed something in this area.”

Western critics of Belarus have expressed concern that tougher sanctions could push Lukashenko further and faster into an embrace of Putin and his calls to proceed with a long-planned “union state” merger of the two ex-Soviet neighbours – and there is evidence that he is now more compliant with the Kremlin leader.

But Lukashenko’s continued insistence on the inviolability of Belarusian “sovereignty” and a revamp of state institutions – including moving powers to the country’s security council, dominated by the president’s son, in the event the president is sidelined or even assassinated appear to indicate a degree of resistance to any bid for his country to be absorbed by its much larger neighbour.